Is My Child Ready for the School-Aged Advanced Swim Program?

You've watched your kid splash through beginner classes. They can do a decent freestyle lap. Maybe they've even earned a certificate or two. When the swim school talks about their "advanced program," you might think: is my child really ready?

It's a bigger question than most parents realise. And getting it wrong in either direction can set your child back.

The gap between "can swim" and "safe swimmer"

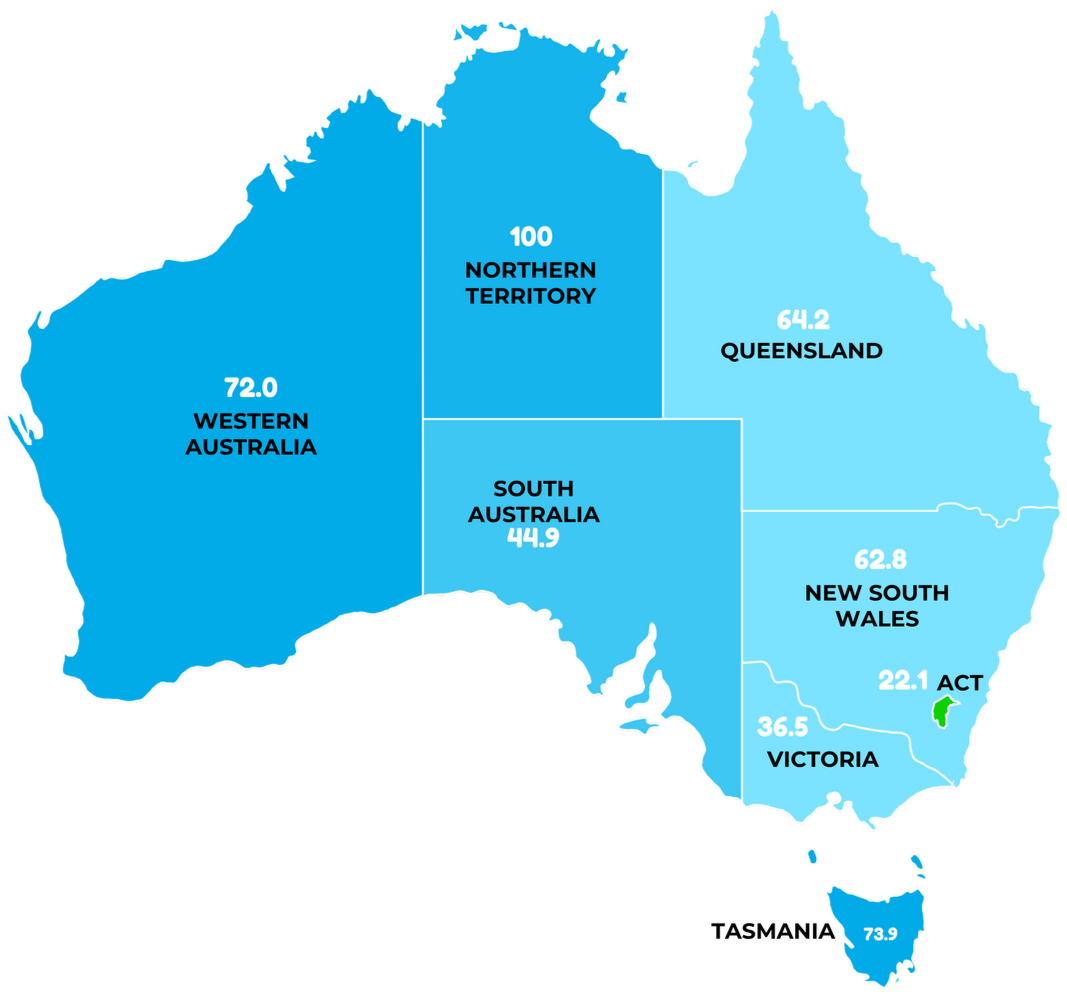

Here's a stat that should make every Australian parent pay attention. Nearly half of Year 6 students cannot swim 50 metres and tread water for 2 minutes. That's the national benchmark for 12-year-olds. And it gets worse as kids get older. By ages 15-16, 84% of teenagers can't meet their age-appropriate swimming benchmark.

Why? Because 75% of children stop swimming lessons before age 9. Long before they've developed genuine water safety skills.

When we discuss if your child is ready for advanced swimming, we’re really asking: are they on track to be a safe swimmer? Or are they about to join the majority who quit too early?

What "advanced" actually means

The National Swimming and Water Safety Framework has three stages for swimming development:

- Fundamental (beginner)

- Acquisition (intermediate)

- Application (advanced)

Your child's current level probably sits somewhere in the first two stages. Fundamental swimmers are building water confidence and learning basics. They can swim about 5 metres, float, and recover to standing . Acquisition swimmers are increasing their distances. They’re also learning different strokes and aiming for the important 50-metre benchmark, along with 2 minutes of treading water.

Advanced swimmers operate at a different level entirely. We're looking at 100 to 400 metres of swimming, 5 minutes of treading water, deep water rescue skills, and survival tasks in heavy clothing. These kids are prepared for real-world water environments, not just pool conditions.

Knowing where your child stands on this spectrum helps you see if they are ready to move forward or if they need more time to solidify their current skills.

Physical signs your child is ready

AUSTSWIM identifies specific physical markers that separate genuine readiness from parent optimism. And yes, there's often a gap between what we hope our kids can do and what they can actually do safely.

Look for coordinated propulsion. This is when arms and legs move together purposefully, not just splashing randomly. Aim for controlled kicks with less splashing. This shows skill mastery, not just effort. Can your child float on their own for 10 to 20 seconds without reaching for anything? Can they transition smoothly from horizontal to vertical in the water?

Breath control matters enormously. A child ready to advance can put their face underwater without feeling scared. They can get in and out of the pool without help. Advanced-ready children also show confidence and comfort in deep water, not just in the shallow end.

Most kids have the skills for formal swimming lessons by age 4. They can usually master front crawl by ages 5 to 6. But here's the crucial point: age is not the primary indicator. AUSTSWIM highlights that readiness means being willing and prepared, not just based on a child's age.

Your 7-year-old might be ready when your neighbour's 9-year-old isn't. Every child progresses differently.

The emotional and mental side

Physical capability alone doesn't cut it. A child may be strong and coordinated enough for advanced swimming. However, they might not be emotionally or mentally ready to move forward safely.

Emotionally ready kids jump into the water without their parents. They are eager before lessons and bounce back quickly from small setbacks. They stay calm during floating activities and handle water on their face without panic. You’ll see them showing pride in their achievements and wanting to go back to the pool.

Cognitive readiness means understanding and following multi-step instructions. It also involves processing technique corrections and being aware of safety rules. Research shows that children aged 6 and older gain the most from complex instruction. In contrast, younger children require simpler and more direct guidance.

Red flags that say "not yet"

Sometimes, the key skill is knowing when your child needs extra time at their current level.

Watch for persistent distress throughout lessons, not just initial nerves. Physical anxiety symptoms, such as shivering in warm water, clenched fists, or erratic behaviour, indicate issues. If your child struggles with new levels, it may mean skill regression. This is an important sign to pay attention to.

Struggling to follow directions or focus in lessons shows they may not be ready to advance. Fear responses, such as widened eyes, dilated pupils, and a racing heart, often signal anxiety rather than just exertion. These are clear warning signs.

Surprisingly, research shows that 19% of negative aquatic experiences happen during swimming lessons. This often occurs when individuals are pushed beyond their comfort zones . Children with these negative experiences recorded lower average achievement at every age.

Pushing too fast backfires. Every time.

Why school programs aren't enough

If your child does swimming at school, that's great. But it's probably not enough.

Research shows children need ongoing weekly instruction to maintain and develop skills. Victoria provides the most thorough approach, but school programs still focus on basic survival skills and safety awareness. They usually don’t cover advanced stroke technique, swimming longer than 50 metres, or ongoing skill improvement.

University of Tasmania research confirms children attending regular weekly lessons at private swim schools are more likely to reach national benchmarks by ages 9-10.

School programs fill gaps. They don't replace consistent swimming education.

The bottom line

Deciding if your child is ready for advanced swimming means considering everything. Physical markers like coordinated strokes, independent floating, and breath control. Emotional signs like confidence without anxiety. Cognitive indicators like following instructions and understanding safety rules.

But equally important is recognising when your child needs more time. Skill regression, ongoing distress, and anxiety show that pressure to advance should pause.

Swimming skills develop in cycles. Children gain skills, then plateau, then gain skills, then plateau. That's normal. The goal isn't rushing to the next level. It's building a genuinely safe swimmer who can handle real-world water environments.

Remember, the shift from parent-child classes to teacher-led instruction can take up to six months. It all depends on individual readiness. There's no prize for speed. Only for getting there safely.

Frequently asked questions

At what age should a child start advanced swimming lessons?

While most children master basic strokes by ages 5 to 6, readiness for advanced swimming is based on skill, not age. Some children may be ready at 7, while others need until age 9 or 10. The key is physical coordination and the emotional maturity to follow complex instructions.

My child swims at school. Is that enough to be considered a "safe swimmer"?

Likely not. Research shows school programs are excellent for basic survival skills but often lack the time to develop advanced stroke technique or endurance (swimming 100m+). Weekly lessons at a private swim school are statistically more likely to help children reach national safety benchmarks.

What are the main skills required for an advanced swimming program?

Advanced readiness generally requires "Acquisition" stage skills: swimming 50 metres continuously, treading water for 2 minutes, and coordinated propulsion (purposeful arm and leg movements with minimal splashing).

My child is showing signs of anxiety before lessons. Should I push them to advance?

No. If your child exhibits persistent distress, physical shivering in warm water, or panic responses, pushing them can cause skill regression. It is often better to pause or remain at the current level until their confidence returns.

Why do so many children quit swimming before they are safe?

Statistics show 75% of children stop lessons before age 9, often because they can swim a lap and parents believe they are "done." However, true water safety—such as treading water for 5 minutes or swimming in heavy clothing—requires training that typically extends beyond the beginner years.